I recently saw a beautiful book about Mercedes. It’s all pure glossy prestige — 400 richly illustrated pages in German, English and French. But there’s a catch…

A translation catch.

The text begins with a story…

Es ist der 19. August 1997, so um 9 Uhr vormittags herum. Die Verbindung funktioniert, auf der anderen Seite der Leitung Herr S…

… with a translation into English:

It’s 19 August 1997, around 9 AM. The link is OK, and Mr S… is on the other end of the line.

… and one into French:

Nous sommes le 19 août 1997, vers neuf heures du matin. Le téléphone sonne, c’est un certain monsieur S… qui m’appelle.

From these translations it appears that the English and French translators don’t agree on the meaning of the German phrase “Die Verbindung funktioniert” (literally “the connection functions”). The English translator has figured that it means that the call has successfully gone through (i.e. it didn’t fail) and that the telephone connection between the storyteller and Mr S… is working.

The French translator, however, has decided that it simply means that the phone rang (“Le téléphone sonne”).

Has an error of interpretation been made? Who is right? How did this happen? What can translators learn from this example? I posed these questions to veteran translator Dr John Jamieson.

John has been a professional translator for more than 35 years working in both the government and private sectors. A native speaker of English, John translates from the majority of European languages ranging from French and German to Slovenian and Finnish. John completed a Ph.D. in French Literature in 1983 at the University of Otago, New Zealand, and has presented his novel ideas on translation techniques at a number of international conferences, including FIT 2014. Currently, John works as the Senior Translator at NZTC International in Wellington, New Zealand.

Paul: What’s going on here, John? Why did the English and the French translators come up with differing interpretations of the original German?

John: The French translator got it right. The phone rang. The English translator didn’t recognise that the German phrase “the connection functions” is a derivative, an oblique expression which refers back to some other specific, concrete event (in this case that the phone had just rung).

Paul: You’ll need to explain what you mean by derivative.

John: This sort of translation problem can be very nicely described in terms of rudimentary calculus. If you have the coordinates of the location of a moving body (such as a train or an automobile), over a period of time, you can calculate its velocity using a simple mathematical rule. If you apply the rule again you can then calculate its acceleration. From position, we can derive velocity and from velocity, we can derive acceleration.

In the example from the Mercedes book, the expression (“the connection functions”) is derived from and refers back to a specific concrete event — “the phone rings”.

Paul: So a derivative expression is more ambiguous?

John: Yes. Just like in calculus, every time you apply the rule to form a derivative, there is some information loss. In this case, the “phone” is lost and we are left with a more ambiguous “connection”. “Rings” is lost and is replaced by “functions”.

Paul: Can you give me some more examples of such derivatives in language?

John: Take for example a newspaper headline which reads, “Former bankrupt to lead the free world”. “Former bankrupt” is clearly derived from “Donald Trump” – but doesn’t say so explicitly. Or, the phrase “Tremor shakes capital” may mean “An earthquake has occurred in Wellington, New Zealand’s capital city”.

The writers of headlines such as these expect you to know the specific information from which they have been derived (that Donald Trump is a former bankrupt and that “capital” here refers to Wellington, the capital of New Zealand). Differentiation techniques like this, however, are culture-bound, sometimes even local dialect-bound…

Paul: … so they often present particular difficulties when they come to be translated.

John: Yes. If the differentiated phrase is translated directly, foreign readers of the text may miss the intended meaning.

Paul: So how can the translator avoid such errors?

John: Firstly, the translator has got to spot that the phrase is actually a derivative (we can talk later about how to do that). Once spotted, the translator may have to modify the expression to ensure it is meaningful to his readers in the target linguistic or cultural context. One choice is to anti-differentiate the phrase.

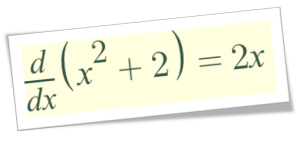

In calculus, the differentiation of functions results in expressions that are progressively less specific. For example, the term x-squared plus 2 differentiates as just 2x. When we try to integrate (or reverse the process to recover the original function from 2x) all sorts of constant elements might potentially be present in the answer.

In mathematics, the reverse process of differentiation, anti-differentiation, is called integration. When you integrate acceleration you get velocity and when you integrate velocity you get position. But integration is not as easy as differentiation because you have to restore the lost information.

This was the approach taken by the French translator in the Mercedes book. He recognised that “connection” was a derivative of “phone” and “functions” was a derivative of “rings” and so he integrated the phrase, restoring the original missing information.

The English translator didn’t recognise that “the connection functions” was a derivative and he rendered the surface, literal meaning in his translation. There is no way that “The link is OK” can be interpreted in English as “The phone rings”.

Paul: So how can translators spot what is derivative and what should be taken literally?

John: As we discussed in our previous conversation the translator can often disambiguate tricky text by establishing where the primary and second stresses lie. Some material in a text is new information, which tends to carry the primary stress, whereas other information is secondary and derivative, referring back to that primary information, and generally carries a lesser degree of stress.

When in doubt, the translator should read the sentence aloud and listen for where the stress naturally falls to make sense. In the Mercedes text, if one reads “Die Verbindung funktioniert” (“the connection functions“) where “functions” carries the primary stress, then we will assume that the literal meaning is the intended one — “Ah! The phone’s working (as opposed to being broken)! This is new information. On the other hand if one reads “Die Verbindung funktioniert”, (“the connection functions”), the unstressed “functions” suggests that the verb here is derivative and is a synonym for something else — “ringing” in this case.

Reading the sentence aloud, trying it with the stress on different words, gives the translator some options. Is there any indication that there was something wrong with the phone line or did the phone just ring? The absence of any suggestion that the phone link was down, indicates that the phase was most likely a derivative of “The phone rang”.

Paul: Are you suggesting that all derivatives need to be integrated when translating?

John: No. The important point is that when translating derivative terms, we must be careful to use expressions that allow the reader to recognise the antecedent it refers back to.

We have to recognise that different languages classify words as derivative differently and we need to select appropriate equivalents in the target language. Hence “les prochaines échéances” will become “elections are next due to be held in…”, or some such (if that’s what the text is about).

Similarly, in a German business text, “die Briten” will be translated as “the UK firm”, not “the British”!

More interestingly, some nouns can be both particular and derivative in one language, but in only one of these categories in another language. Thus “measure” in English is a derivative concept, whereas the literal equivalent “Massnahme” in German can be quite specific. If a German company has decided to implement a “Massnahme” to address a problem, we might translate this as “countermeasures”, “programme”, even “set of measures”, etc.

Similarly, a conference paper, or a telephone call, could be called a “communication” in French, whereas English “communication” is usually a derivative word. Similarly “Beleg” in German tax correspondence usually means “receipt”, “invoice” or both, as a primary function concept. Many dictionaries give “document”, but that tends to suggest a derivative term, and the English reader is left wondering what (already known) document is being referred to.

As translators, we have to distinguish between primary and secondary beats in the text, to detect what is new and what is derivative and then reflect the different weightings of the two categories in the target language. This may involve some manipulation of the text and the restoration of some “missing information” — something that would not be approved by some of my colleagues in the profession, and indeed by some translation examiners.

Even the most boring, everyday texts are imbued with their own form of prosody and music — strong and weak beats dictated by the semantic flow of the communication. Reading difficult texts aloud to find these beats, as musicians do when they read a score, can enrich the reading experience, particularly in the case of good or great writing.

There’s just one (tiny) problem. With ‘die Verbindung funktioniert’ you don’t know who’s calling who. Thus the French translation ‘le telephone sonne’ gives you an information that the original (German) text doesn’t give you. As the caller/speaker may hear the ringing after having typed Mr.S’s number. You still don’t know who’s calling who. Which you may/should know after the first verbal exchange.

Interesting thought, even though it’s a “leaky” abstraction (cf. https://www.joelonsoftware.com/2002/11/11/the-law-of-leaky-abstractions/)

Are you sure that the French translator took this right? Technically, the connection works means that the caller got the line, possibly receiving a dial tone, not necessarily that the phone of the intended recipient of the call rings. The link could be OK, but the telephone might not ring, e.g. if the dialed number is busy. Logic (common sense, actually) and differential calculus do not match, in this case.

This might make sense perhaps if the author was the caller. However, the wider context is that the author was in his car when his phone rang. So he answered the call – it was his publisher offering him some work. Occam’s razor here, I think, Luigi: The phone rang.

Some very interesting points there. Although not exactly a “hard science,” translating is certainly hard enough to get right. I wish it could be broken down to a mathematical formula.

Amazing book, Mercedes is my top brand across all cars, very interesting reading.