Are translation industry players locked into a self-defeating paradigm where they end up taking actions which are against their own best economic interests?

Are translation industry players locked into a self-defeating paradigm where they end up taking actions which are against their own best economic interests?

In this post, I look at the translation industry in terms of a prisoner’s dilemma—the canonical example of a “game” from the branch of mathematics which concerns itself with strategy and decision-making known as “game theory”.

Over the years, the prisoner’s dilemma has provided many great plots for some well-known TV dramas and movies. A serious crime is committed and a couple of bad guys are caught by the police. The cops do not have enough evidence to convict them, so the suspects are interrogated separately in the hope that they will betray each other [1].

If the suspects keep their mouths shut, they’ll get convicted on a minor charge and will spend only minimal time in jail. However, if one of them confesses and implicates the other in the crime, he’ll go free (while his partner will get a long stretch in jail).

However, there is a catch—if they both rat on each other, they’ll both get the full prison sentence.

So what would you do? Your partner in crime is being held in a separate cell, so you can’t talk and agree on a joint strategy. Will you decide to keep your mouth shut and trust that your partner will do the same? Or do you think that he will betray you? If you think that you can really trust him to keep quiet, then you have the option of double-crossing him—and get rewarded with an immediate release from jail.

But isn’t that what he is thinking too?

£100,000—Split or Steal?

How do real people tend to solve this awful dilemma? Watch this short video clip from a British TV game show for an electrifying answer:

The analysis

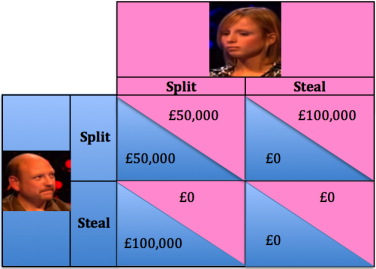

Was Sarah just lucky or was her decision completely cool and rational? Look at the so-called “payoff matrix” in the table below. Here you can see Sarah’s payoffs (in pink) if she splits or steals given Steven’s two choices.

Looking down Sarah’s left-hand column, we can see that if she chose to split the money, she would either get £50,000 (if Steven also decided to split) or nothing (if Steven decided to steal). When we look down her right-hand column, we can see that if she chose to steal, she would get either £100,000 (if Steven decided to split) or again nothing (if Steven decided to steal).

Whether she goes home with nothing or with some money in her pocket depends entirely on Steven’s decision. If he decides to steal, then there is absolutely nothing she can do about it—she will just get nothing whatever she does.

So for Sarah, the whole game reduces to deciding what to choose in the event that Steven decides to split. Her options are simply to choose between £50,000 and £100,000.

Which would you choose—the smaller or the bigger amount?

For most people, this sort of decision is a no brainer. Leaving aside any moral qualms, we can see that Sarah’s decision to choose the bigger sum over the smaller sum is the only rational one.

So she has to steal.

But what about Steven—Mr Nice Guy? He too had the same choices as Sarah. As a “nice guy”, he could clearly see that the best outcome for both himself and Sarah would be to cooperate, and to share the money equally. Cooperation would ensure a happy, win-win outcome. As it turns out, (and to use a technical term from game theory), he ended up with the “sucker’s payoff”.

Now, what about the two prisoners being held in separate cells? Do they typically cooperate by both keeping their mouths shut to ensure a nice win-win outcome? Or do they end up ratting on each other hoping that this will buy them a get-out-of-jail-free card?

Clearly if they cooperate they will both be better off in the long term with only minimal time in jail. One of them might want to keep his mouth shut, but can he trust the other guy to do the same? Or will the other guy double cross him? On the assumption that they are just as rational as Sarah was on the game show, the logic of the situation demands that the best strategy is to rat (or “steal” in Sarah’s case). Real life experience shows that “ratting” is the most typical decision for both of them—a decision that both suspects will have plenty of time to regret during their long prison sentences.

Only in hindsight is it easy to reflect that cooperation would really have been in their long-term interests.

But… do translators do this too?

Now let’s cast Sarah and Steven as the owners of two mid-sized translation firms and see if we can find them playing out this sort of “prisoner’s dilemma” drama [2].

On the Island of San Esperito, there are a good few translation companies—the two dominant players are Sarah’s Global Translations Ltd and Steven’s HiQual Languages Inc. These rivals promise their customers that they can deliver translations of the highest possible quality into any of the world’s languages in virtually any subject field. Each year they vie for the work from San Esperito’s biggest translation buyers, the local Tourism Board and a large local software development company, Touch-Tech Ltd.

Both firms have figured that an “average translation job” from the major buyers is around 3,000 words and that each buyer orders around 1,200 jobs per annum. The translation firms source the linguistic work from the global pool of freelance translators for a little less than 7 San Esperito dollars per hundred words—so the cost of an averaged-sized job to each firm is around $200 [3].

The firms also know that they can charge their customers somewhat over $26 per hundred words. So they figure that if they charge $800 for an average-sized job, each firm will make a gross profit of (800 – 200) x 1,200 jobs = 720,000 dollars per annum.

From experience over the years, the firms have figured out that if one of them drops its average price by $10 (and the other keeps its price unchanged) then the price-cutter is likely to get another 100 jobs—80 jobs that would otherwise have gone to their rival and 2o jobs from new customers.

This alluring fact of life provides an ongoing temptation for each firm to undercut its rival.

The dilemma

To make our story simple, let’s suppose that each of the two dominant firms in San Esperito can choose between just two prices—the “normal” price of $800 and a cut-rate price of $700 for an average-sized job.

If Sarah’s firm decides to drop its price to $700 (while Steven’s firm is still charging $800), then Sarah stands to get an extra 1,000 jobs and Steven will lose 800. Sarah would end up with 2,200 jobs per annum at a great profit of $1,100,000. The work load at Steven’s company would sink to just 400 and his gross profit would plunge to $240,000. This could provoke a life-threatening situation for Steven’s company if this amount didn’t cover all his firm’s overhead expenses such as rent and administration salaries etc.

Now what happens if both firms cut their prices? At this lower price, they’re unlikely to lose their existing customers and both firms will attract another 200 new jobs away from some of the smaller local translation agencies. With 1,400 sales each averaging $700, both Sarah and Steven are now each looking at a gross profit of $700,000.

By comparing the pairs of payoffs in the four cells above, we can see that a better outcome for Sarah sometimes means a worse outcome for Steven—but not always. When they both charge $800, they are both better off as we can see in the top left-hand cell.

Since they are both better off charging the higher price, is that what they end up doing? When Sarah is considering her pricing policy, her thinking is going to be the same as it was when she was playing the TV game show:

“If Steven prices his work at $800 I can boost my profit from $720,000 to $1,100,000 by cutting my price down to $700. On the other hand, if Steven also decides to go for $700, then I’ll only make $700,000. But if he drops to $700 and I keep my prices high, then I’ll really be in trouble and I will only make $240,000! That could be really dangerous and could put my business at risk. I’d probably not be able to pay the rent and I’d definitely have to squeeze the freelancers’ rates.

So I can just ignore what Steven does. Whatever he does, I’ll always be better off if I charge $700.”

Is Sarah’s logic correct? Check it out by looking across the rows in the table above:

- If Steven charges $800, Sarah is better off by charging $700 (a $1,100,000 profit is better than a $72,000 profit).

- If Steven charges $700, Sarah is again better off by charging $700 (a $700,000 profit is better than a $240,000 profit).

In game theory, Sarah is said to have a dominant strategy—that is a strategy that always delivers the best outcome whatever the other player decides to do.

But, Steven also has the same dominant strategy! He too is always better off by charging $700 irrespective of what Sarah decides to do.

Assuming that the decision makers in both firms are cool and rational, they will both end up playing their dominant strategy ($700) and they will both end up making a smaller profit than if they had both decided to stay with $800. (This is precisely what the criminal suspects tend to do—they both rat on each other and they both end up for a long stay in jail.)

Acting against one’s best interests…

When both Sarah and Steven use their dominant strategy, they both do worse (at $700,000) than they would have if somehow they could have jointly and credibly agreed not to use their dominant strategy but rather kept their prices high at $800 (when they would have made $720,000 each).

As we saw in the game show, Steven is a really nice guy and earnestly tries to do the right thing in the best interest of both parties. Unfortunately Steven’s attempts to keep the prices up will soon cause his business to collapse as the temptation for Sarah to drop her price and make a huge profit is just too compelling. It’s not enough for just one player to be the good guy…

Is there a solution to the dilemma?

Both LSPs (regardless of their size) and freelance translators are ensnared in a prisoner’s dilemma. So how do we get translation industry players to cooperate and stop cutting each others’ throats? Can they collaborate and yet still compete? [4].

Are there actually any realistic strategies which motivate competing players to break out of this self-defeating game and take actions which are in their long-term interest? Or is that just a pipe dream?

In my next post I talk to my friend Luigi Muzii [5] about some solutions to this vexing game.

Notes:

[1] The cops’ better knowledge of how the system works puts the suspects at a distinct disadvantage as they try to figure out what best to do. This sort of information asymmetry also plays a role in the translation industry when buyers try to figure out the quality of the services they buy. This topic is discussed here: The price of translation – why is it like buying a second-hand car?

[2] The example scenario given here has been freely adapted from The Art of Strategy by Avinash K. Dixit and Barry J. Nalebuff, 2008, (Chapter 3), W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York, N. Y. 10110.

[3] The idea here is that this is “marginal cost” (i.e. the change in the total cost that arises when the quantity produced changes by one unit.) The profit in this example is therefore gross profit and therefore does not take the firms’ fixed costs, such as rent and other overheads into account.

[4] The beneficiaries of price wars, of course, are the buyers, who are not active players in this game. It is often in the larger society’s interest to prevent competing firms from resolving their pricing dilemmas—this is the role of antitrust policies in many countries.

[5] Luigi Muzii is a well-known commentator on the translation scene with deep insights into the economic drivers that bedevil the industry. See a short biography here: http://www.slideshare.net/muzii

Pingback: Collusion and betrayal in the translation indus...

Impressive, intriguing and inciting post. Took me some resilience to read it all, I must say. But it was worth it. Already looking forward to the next “chapter”.

Kind regards,

Nicole

But isn’t it the case that buyers just ask for a discount, the refuse to pay the 800$, and then wait for best offer? So Sarah & Stephen have to guess what discount the other one is offering to stay competitive? LSPs are competing with each other because of this, and not with translators whom they are buying from?

I would say from my understanding that I think competition (which is not out of control) is a good thing – for the buyer and for market innovation. However, competing on price alone… is not a good idea as as a business you start to change your core strengths/competencies. Some ideas of strategy come to mind (such as Bowman’s strategy clock) and I wonder, is it more a question of the right target market?

Some of use would like cheap plane tickets, but there is a certain level of quality, speed, flexibility, service and safety we expect.

A thoughtful, thought-provoking post. Thank you for providing an excellent tool for explaining a critical issue to colleagues. I’m definitely looking forward to Luigi’s post.

Agree that lowering our prices will only keep us on an endless race to the bottom, TSPs that keep lowering the price are shooting themselves.

Pingback: Nice or nasty? Which translators finish first? | The translation business

Pingback: Weekly favorites (Aug 26-Sep 1) | Lingua Greca Translations

Funny, intrigued by the dilemma, nobody has noticed that both firms use false (deceptive) advertising: “These rivals promise their customers that they can deliver translations of the highest possible quality into any of the world’s languages in virtually any subject field.” while sourcing “from the global pool of freelance translators for a little less than 7 San Esperito dollars” . “Highest possible quality”, oh, my ears and whiskers!

Extremely interesting reading, but you forgot to include the most likely scenario: after dropping their price to $700, both Sarah and Steven will write to their pool of translators claiming that times are hard and asking them to drop their rates from 7 Esperito dollars to 6. In fact they will most likely do this whether they drop their agency prices or not. That skews your calculations a little bit doesn’t it?

Hi, this is my first time in your blog. Very nice article about translation industry. Keep going